Data Science Isn't

A classic use of data science at a technology company is a feature A/B test to improve revenue or engagement metrics.

It goes like this:

- Ask a question: can we drive more users to pay for our product by changing, say, the color of the sign-up button?

- Formulate a hypothesis: what if we make it a big grey button? A big red button? A big flashing red button?

- Do an experiment: implement each of the variants and randomly assign some visitors to each one, measuring the signup rate under each hypothesis.

- Analyse the results: perform a mathematical ritual which determines if the changes made a “statistically significant” difference in sign-up rates. Interpret this to mean that the resulting sign-up rate is not simply due to random variation, and identify whether the winning variant actually caused more sign-ups to happen.

- Conclude things: if one of the variants clearly emerged as a winner, commit to that result and remove the others from code. Don’t forget to also mass-email folks and show off the results of your experiment and claim credit for driving X% signups / revenue / whatever. Good on you, promotions all around. Stick it on your resume.

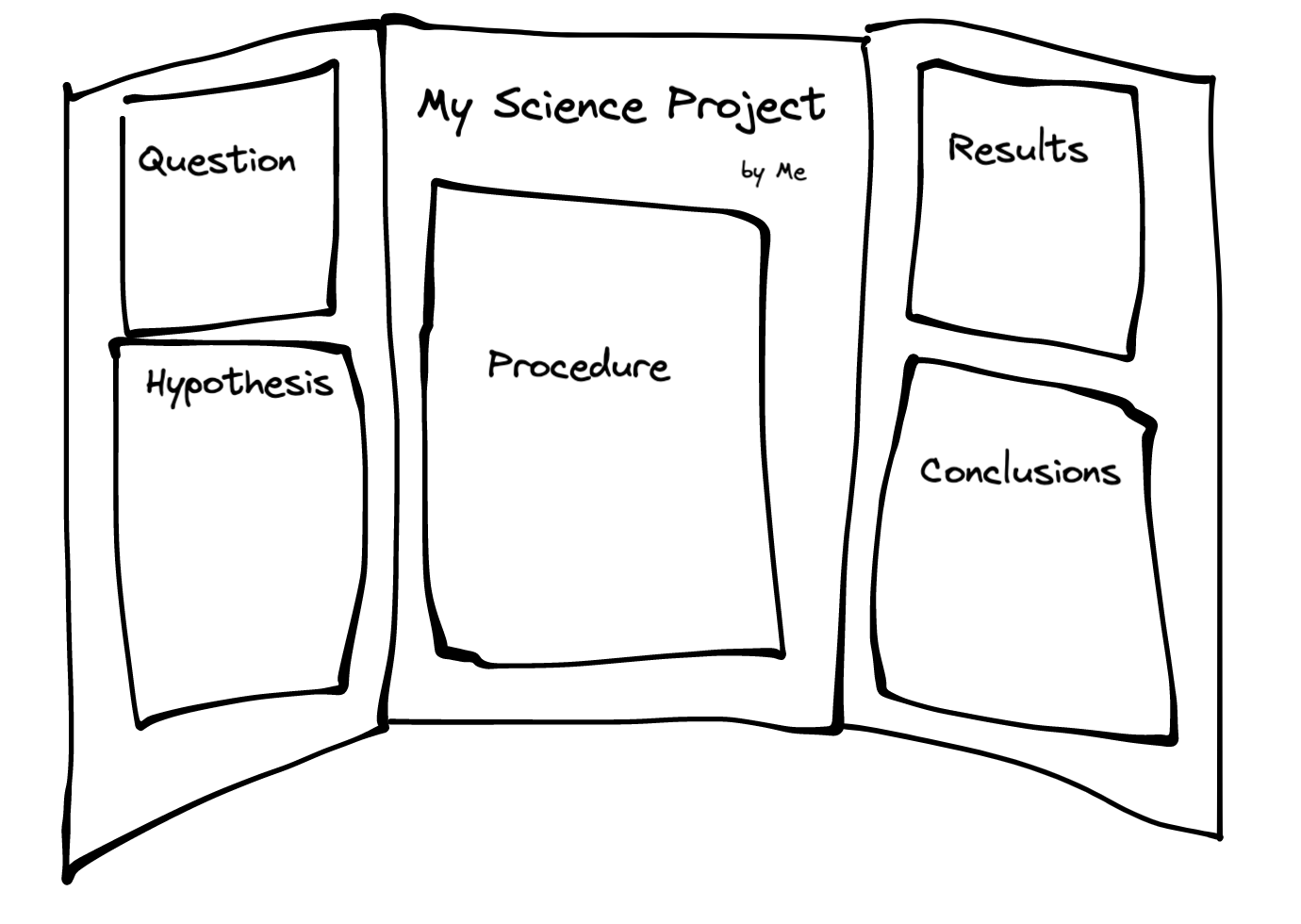

We might call this the Data Science Scientific Method. It certainly looks like we did science—after all, isn’t this how science worked on those triptychs in middle school?

Everybody knows that Science is Good. Why is it good? Because it’s the only way to be right, which means systematically avoiding bias, guesswork, and blind spots. Fortunately everyone at the company also knows that that everybody else knows that Science is Good, so there’s no need to even discuss it. Instead we can carry on with doing science, being right, and making money. We know it’s right because it’s working: science is getting good results, converting customers, earning promotions, and making lots of money. Everyone can be very pleased that they’re part of big rational money-making machine which is smarter than any individual.

…

Two problems with this:

- That’s not actually what science is.

- That big rational machine is somehow dumber than a single person.

You know what data science “experiment” I’ve never seen anyone do?

Test the question “can one person, using their intuition and maybe asking around a bit, make better decisions than our whole data-driven experimentation ritual?” Cause if so, then maybe you should just give that person all the decision-making power and do whatever they say for a while. You’ll save a lot of money on compute alone.

Or, do better science. Science is, indeed, about being right. Just because you did a thing that you called Science, and which everyone thinks is Science at a New-York-Times-reader level of understanding, doesn’t mean you’re right. The fact that you made money successfully doesn’t even make you right! At best you were provably right at the small question of “which of these colors of button gets more clicks over the next little while?”; probably not at the bigger question of “what’s the optimal way to make more money?” and definitely not on the even-bigger question of “what’s the best thing to do for the business to succeed?”

What Science Is

It’s not this:

- Ask a question

- Formulate a hypothesis

- Do an experiment

- Analyse the results

- Conclude things

Science is not a formulaic process anyway, at least not really, but if it was, the most important aspect of the formula is that it has the property of converging on better understanding over time. Anyone who becomes knowledgeable and correct and efficacious over time is doing something scientific, no matter the setting or their precise process. That is both the reason that science is usually more correct than random idiots, and also the reason why it’s not always correct. Science isn’t right by fiat—but on average it does get righter whereas random idiots do not.

So the formula we come up with better involve feeding back into itself and doing a better job with each iteration. With that in mind, here’s a better list of steps:

- Learn a lot. Observe and study the world.

- Conceive of a model of the world that makes sense from what you know.

- Ask a question (that your model has something interesting to say about…)

- Formulate a hypothesis (about what answer your model would give if it were correct that other models would not give)

- Do an experiment

- Analyse the results

- Conclude things (about the accuracy of your model)

- Update your confidence in your model based on the result.

- Go back to step (2) until your model is good enough for your purposes.

- Go and do things in the world using your model now that you know it’s good.

If you don’t formulate a model as you go, or use your experiments to test and improve that model, you’re not really doing anything that deserves to be called Science. You’re just doing… experiments, in a loop, without ever learning anything? You’re certainly not improving on your model over time.

As I see it, corporate data science isn’t ‘science’, because it isn’t really about building models or being right in the first place. Its real job is to make decisions. Or more precisely, to launder decisions: to make the decision-making process so benign and agreeable that nobody risks blame, for making mistakes or missing opportunities. You want me to understand how users’ minds work and then pick what color the button should be? But what if I’m… wrong? Better to let an experiment decide for us— nobody ever got fired for making the button whichever color people clicked on the most for two weeks last June.

Science is—has to be—the process of studying things in a way that necessarily becomes more correct over time. Asymptotically it should figure out the true workings of whatever slice of reality you’re looking at. This always involves building up theories of how reality works, and typically should require validating those theories with experiments to see how good they are, although, strictly speaking, that’s only useful inasmuch it gets you closer to correctness; you can get away without it sometimes.

In business, the theories are answers to the question “how should we run our company?”. That is, “what should all these people do?”. That experiment to see what color the button should be? It assumes, but never checks, that the answer to that question is this: “we should run experiments like this one all day and then do whatever they say into the future” You could also do some science on that hypothesis, if you wanted, but don’t bother; it’s pretty obviously wrong. We have plenty of evidence already: everywhere you look, data-science-driven companies are doing fantastically dumb things, and everybody who works at them knows it (and will happily tell you, with pained resignation!). And yet these companies carry on with their foolishness anyway—because their collective understanding is that they’re supposed to stay carefully on the sacred data-driven path.

Why are they able to go on being so wrong?

I think that in the end the problem is a near-complete absence of leadership.

Leadership

How do you do a better job at running an organization than a bunch of make-believe science experiments?

For starters, write down and aggregate all the results of your little experiments in a way that can be used for future decisions, and then use that knowledge to actually make future decisions—in lieu of further experimentation. If every “no thanks I don’t want to buy your shit” button should be grey and invisible to press the psychological buttons that make you more money, and if doing so passes your own ethics (treating your customers with respect is, perhaps, not relevant here…), you don’t really need to test the next one. You already know! It will work! That’s what the science was for!

“That sounds nice,” you think, and yet… a few quarters later… somehow you’re back where you were, doing that same experiment again, testing variants of buttons and user flows and whatever, even though it’s obvious how to make improvements without testing them. Why?

Well, it turns out there’s another reason people do this “science”, and it’s probably the main reason: it’s that they need to be able to take credit. If you knew the button color would help the business and your job was just a regular job where your responsibility is to do a good job at something, you’d just change the color to the color it should be and that would be it. But if you need to argue about getting a promotion, you need to attribute that revenue to something you did, because your annual review is gonna say “drove X% revenue growth via <a series of changes>” and if you don’t know how much you drove you can’t put it in there. Even if, and this is the super-aggravating part, the thing you did was obvious and the experiment was a total waste of time and money.

The only people who are really in a position to put a stop to this are the people are who doing the evaluations of other people’s work. They should be smarter: smart enough to see that the experiments were a waste of time, smart enough to see that the conclusions reached were foregone and unhelpful, and especially smart enough to enough to see that “doing good work” isn’t the same as “getting good measurable results” and is in fact probably the opposite of it. In fact the best work most often consists of what you build, grow, and polish using your volition and grit, and those are all (a) easy to see and (b) hard to quantify.

But as long as the evaluators don’t believe this is their job, we’re stuck. They’re trapped in the same cycle: they’re accountable to someone else who wants everything quantified numbers also, and they’re beholden to some rubric for evaluation, and even if they wanted to go rogue, there’s no actual culture in place of evaluating things on their merits and in fact they’ll get ridiculed and reprimanded if they try. Their boss? Same thing. The problem infects everything, and unfortunately ends up landing on least accountable group of all: the shareholders, an amorphous machine that only cares about everyone else believing the numbers are real for a while so they can sell at a profit.

If you keep following this train of thought you end up in a weird subterranean viewing chamber where you gaze into the obsidian boulder and see reflected in it one of the dark truths of corporate capitalism: that everything, products and performance reviews and promotions, design and engineering and marketing and the rest, are all about avoiding making any kind of decisions whatsoever, or taking any personal risk at anything. Everybody has offloaded all responsibility… for everything… onto math.

It is a farce. Is this person a good manager? No idea! Did they help people grow, or do more than the bare minimum at every step, or build something that will last? Can’t remember! Does it matter how good their management was? Who cares, what we want to know is, did they do measurable things to benefit the company? Heck yes, and we proved it with science! Nice. Bonus secured.

The Question of Fallibility

A common reaction is: well, the reason they’re doing all this math is that people are biased and fallible and math has at least a hope of avoiding that. In fact in the past they did all sorts of things without math and it was even worse. Right?

And I agree. Don’t get me wrong: if these same people one day started “making decisions”, leaving everything else unchanged, it would be disastrous. People can be really, really dumb. Especially people who have never had to do a good job at decision-making before. The people in charge today largely got where they are without having to prove themselves by making lots of smaller decisions first. It was rarely a requirement to be any good at leadership at all.

But I don’t think it’s impossible to do better. What’s missing is leaders being accountable for their competency as leaders. That’s why, among other things, it’s absolutely necessary to support unionization and internal protests and anything else which involves taking power away from leaders who don’t deserve it. A leader should have to earn the right to lead at any level and should have to keep earning it to continue leading, which means that the people they’re leading need to have the right to take it away from them. For bizarre reasons Western culture seems to think that people should get to stay in charge of something because they built it. I disagree. Once you become responsible for a bunch of other people’s life’s work, we have a right (not yet enshrined in law, of course) to depose you if you don’t do a really good job of it.

If anything, the modern cargo-cult data-science is probably a reaction to the last age, a time when tyrannical executives roamed the earth, doing whatever insanely dumb shit they wanted, checked only by the whims of their also-tyrannical superiors. Words like “systematic bias” or “logical fallacies” hadn’t been discovered yet, so there wasn’t even language to explain why they were so wrong. And they had those positions not because they were the best at what they did, not because they earned it with hard work, but because they were, like, the right type of well-groomed white dude who looks good in a sportcoat. I’ve heard it’s still like that in many parts of the world. But, you know, not in modern corporate America—we’re better than that. We use data now!

In a way, handing decision-making over to what is essentially an algorithm is a way of taking power away from powerful people and getting them to somehow go along with it. Which doesn’t sound so bad, really. If anything it’s the theme of the last century of progressivism.

Yet the result is, in a way, shameful. The organization is still clueless, only now it can’t as easily blame anyone for its clueless floundering. This arrangement can actually afford the people in power more protection: they’re less culpable for the consequences of their actions, because they don’t take actions. They still fail… but everything was decided by the data science. In fact everybody, in power or not, can say this: we just did what the data told us; we did everything right! Especially in tech, where money and therefore validation just blows your door in if you leave it unlocked, these organizations can’t even tell how dumb they’re being. It all seems to be working! They’re still getting conversions; people are clicking on the ads; the stock price is good. When in fact the actual test of your hypothesis about how to run a business happens on far too slow a scale to get any feedback—decades, I guess. However long it takes a company to rot at its core, wither for a while, and finally go bankrupt. As long as the economy is good and the industry is ascendant, everybody gets plenty rich from mediocrity.

Well, fine. I, for one, don’t enjoy being part of this money-grubbing idiot machine at all. It’s no fun to spend your one life’s effort on stupid work. And even if you somehow avoid this fake science in your job, every product you use has already been ruined by it anyway (look no further than “every recommendation algorithm”). You would have to go live by yourself in the woods to get away from being affected by decisions that are obviously bad to everyone but looked good enough in the metrics. (Don’t even get me started on things that are actually good ways to make money but are totally evil you’d be ashamed telling your kids about. “The data told me to do it!” I bet it did.)

But hey. Maybe it’s a good thing that we’re already getting used to the idea of offloading all responsibility onto a machine we built to rule us. That might turn out to be serendipitous. :thinking-face: