Weird Takes on Angles

Special edition / rare vintage math facts that I found interesting. Not your everyday stuff. Somewhat kooky. Grain of salt, etc.

Also playing around with doing diagrams in Excalidraw with its not-yet-released LaTeX plugin, which is janky but very quick to use. But it can’t do that much so I’ve had to be sloppy in places. It’s better than getting blocked on the pictures because they’re too much work, though.

1. Angles

What “is” an angle?

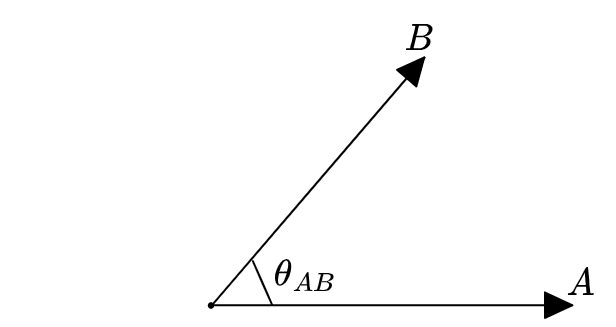

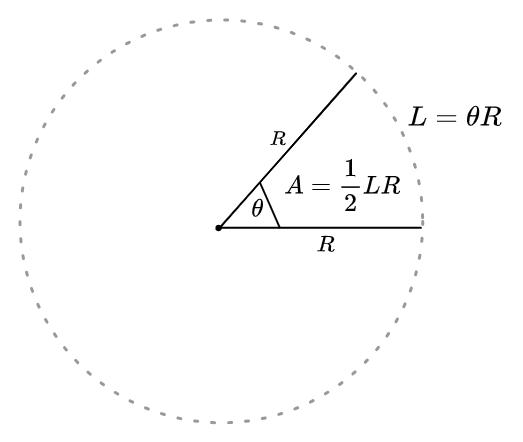

Well, it’s the portion of a circle swept out between two directions:

Our choice of units \((0, 2 \pi)\) or \((0^\circ, 360^\circ)\) are arbitrary; they reflects how we choose measure the quantify the length of that part of the circle. We could even just use units that go from \(0\) to \(1\): from none of a circle to all of it (sometimes called “turns”). I like to write the total angle of a circle as \(\bigcirc\), a symbol, rather than its value in some units, so that the formulas stay unit-agnostic.

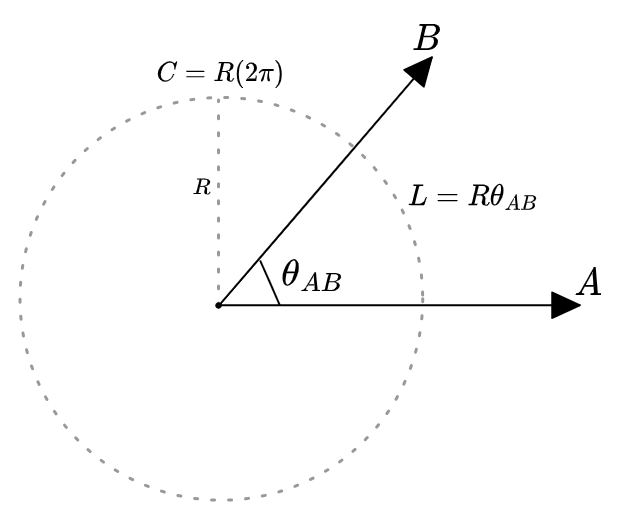

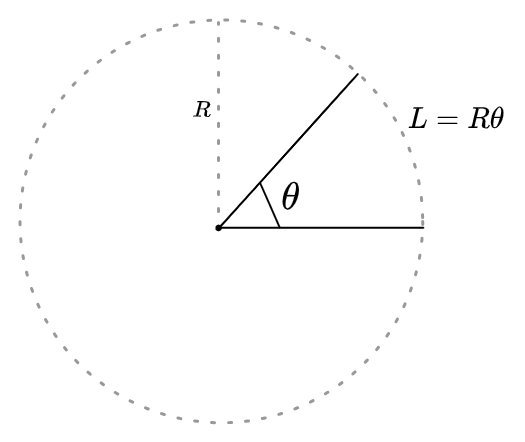

Although there is something special about radians. They give the measure of that arc in terms of its length on the unit circle, which means that the length of the circular arc that’s swept out, if it’s part of a circle with radius \(R\), is given by the fraction of the total circumference \(C = \bigcirc R = 2 \pi R\):

\[L = \frac{\theta}{\bigcirc} C = \frac{\theta}{2 \pi} (2 \pi R) = \theta R\]Or, to go the other way: a circle is equivalent to an arc of angle \(\bigcirc = 2 \pi\), and its circumference is therefore \(C = \bigcirc R = 2 \pi R\).

I say that there’s something speial about radians because they seem to get special treatment in math. For instance the Taylor series \(\cos \theta = 1 - \frac{\theta^2}{2!} + \frac{\theta^4}{4!} - \ldots\) would look rather pitiful if you meant for \(\theta\) to be measured in degrees:

\[\cos \theta \? 1 - \frac{[ \frac{2 \pi}{3 60^{\circ}}\theta]^2}{2!} + \frac{[ \frac{2 \pi}{3 60^{\circ}}\theta]^4}{4!} - \ldots\]Clearly nature prefers radians. (Although if I’m being honest, I still like the \((0,1)\) units. It would not upset me that much if that formula had \([2 \pi \theta]^n\) in it everywhere.)

It is interesting to think that the “units” on a circumference have a factor of radians in them. If we were in degrees, would it be \(360^{\circ} R\) instead? Well, that would be like measuring linear area in foot-meters. It’s valid, but it’s dumb, and you’d want to convert your degree-meters to radian-meters in order to actually use them.

Radians are a funny kind of unit. Some people would say that they are not true units. I disagree, but they’re definitely not the same kind of units as the other ones. But even if they are units, maybe it seems like the circumference, a “length”, should be measured in meters, not radian-meters. Which means that maybe the true formula for the length of an arc of angle \(\theta\), measured in radians, ought to be \(L = \frac{\theta}{\text{[rad]}} R\). Unfortunately that’s awkward too. There’s an argument to be made that it’s wrong, and it was correct as-is, but… that’s for later.

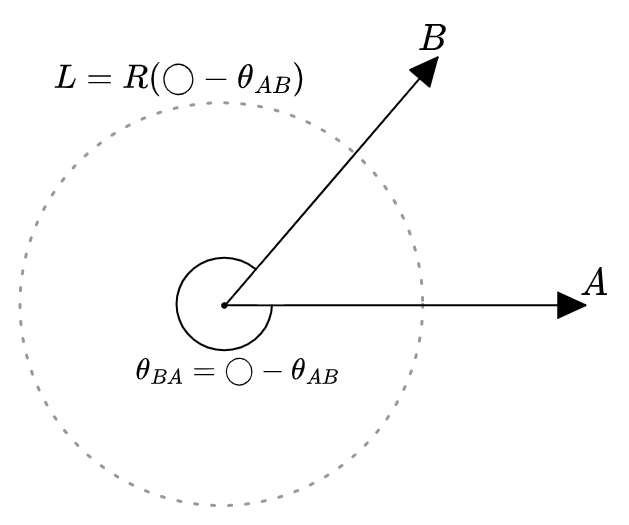

Regardless of the units, the opposite side of an angle is going to have angle equal to \(\bigcirc\) minus that angle. That way we don’t have to make a choice of units in our diagrams:

Naturally we call the exterior angle here \(\theta_{BA}\), since it’s the angle you get if you go from \(B \ra A\) instead of \(A \ra B\). Although it is a little weird that you could also go backwards, from \(B \ra A\) the other way? Fortunately, the values of angles do not take values in \(\bb{R}\), but rather in

\[\bb{R} \; \text{mod}\; \bigcirc\]That is: \(-\theta_{AB}\) and \(\theta_{BA} = -\theta_{AB} + \bigcirc\) are “the same value,” as far as circles are concerned.

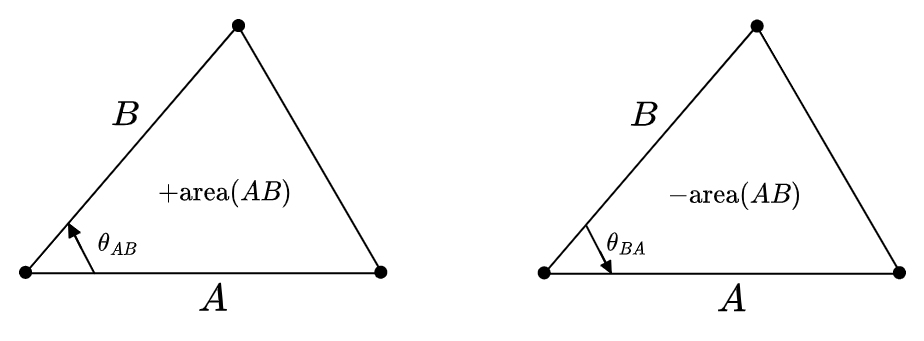

Nevertheless it can be helpful to think of an angle as having an orientation, which means that we differentiate going “up” by \(30^\circ\) and “down” by \(30^\circ\), depending on which line we start at. The positive direction is CCW, the direction that radians and everything else in math goes go up in. This way: \(\circlearrowleft\). So we could also write

\[\theta_{BA} = -\theta_{AB}\]This says that our angles are oriented angles, which are an under-utilized concept. Among other things they play nicely with oriented areas: a positively-oriented triangle has a positively-oriented angle and positive area, while a negative oriented triangle has a negatively-oriented angle and negative area:

\[\begin{aligned} \area(BA) &= \frac{1}{2} \| A \| \| B \| \sin \theta_{BA} \\ &= \frac{1}{2} \| A \| \| B \| \sin (-\theta_{AB}) \\ &= - \frac{1}{2} \| A \| \| B \| \sin \theta_{AB} \end{aligned}\]

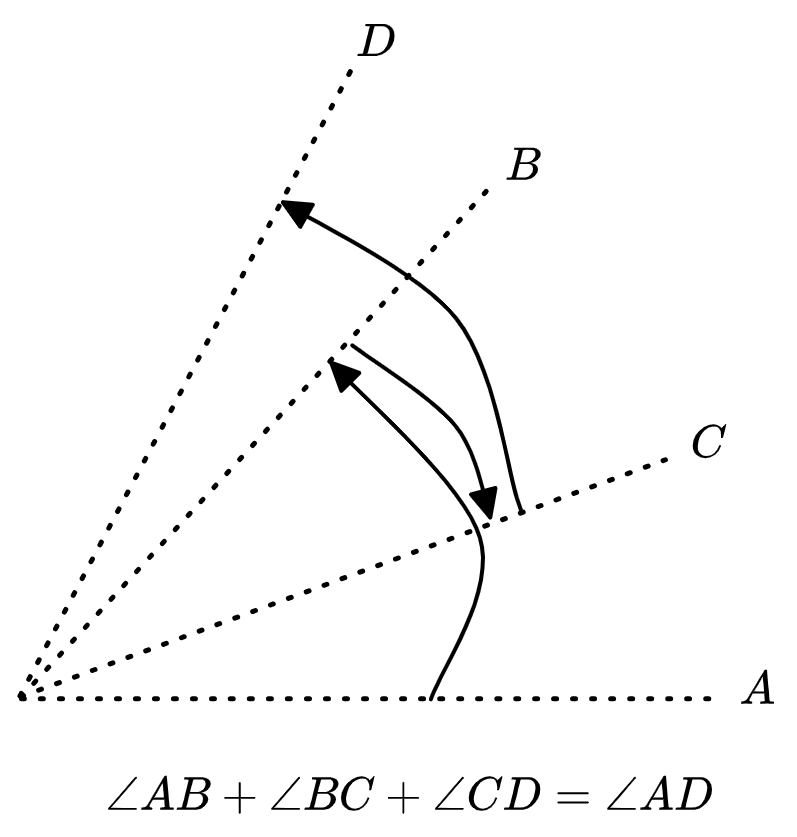

You can add and subtract oriented angles like they’re vectors:

forgive my janky arcs

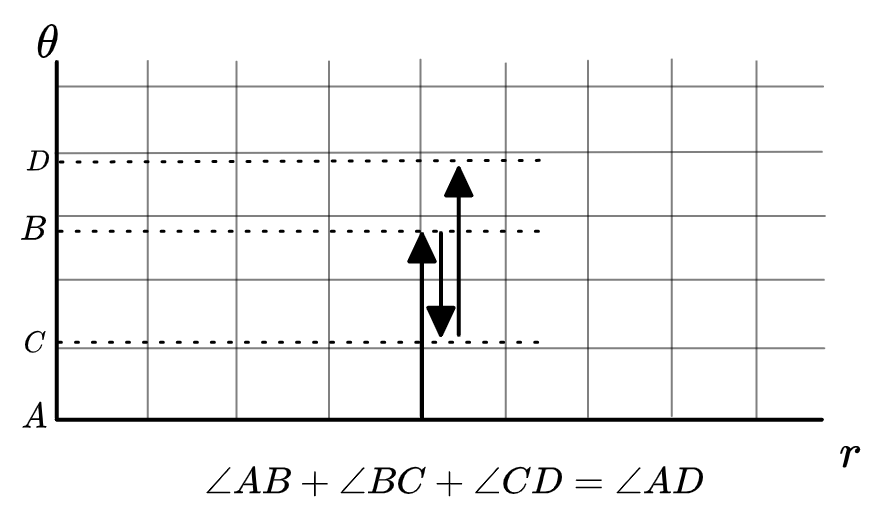

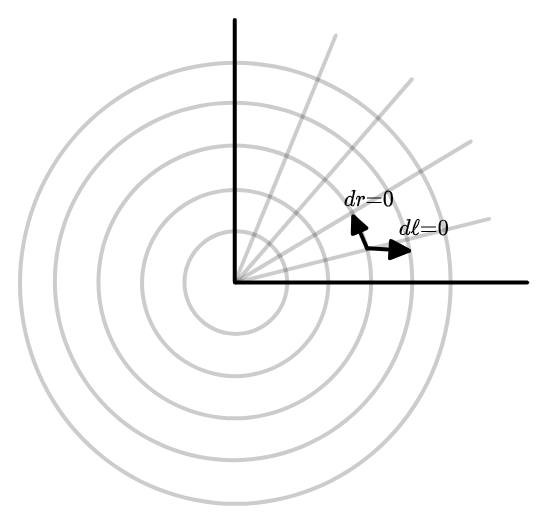

That’s just because they are vectors: angles are displacement vectors in polar coordinates. Just like you translate \((5 \b{x}) + (3 \b{y}) + (-1 \b{x}) = (4 \b{x} + 3 \b{y})\) in rectilinear coordinates, you can add up in translations in polar coordinates. We can draw the polar coordinate grid as a rectilinear grid instead:

Now it is easy to see that we are just doing vector addition in the \(\theta\) coordinate. Of course angles should be oriented.

2. The Area of Arcs

Now, an angle measures the fraction of the total circle \(\bigcirc\) swept out by an arc.

This means the area of an arc of angle \(\theta\) with side-length \(R\) is the same fraction of the area of a circle with radius \(R\). The circle of course has area \(\pi R^2\), meaning the arc has area

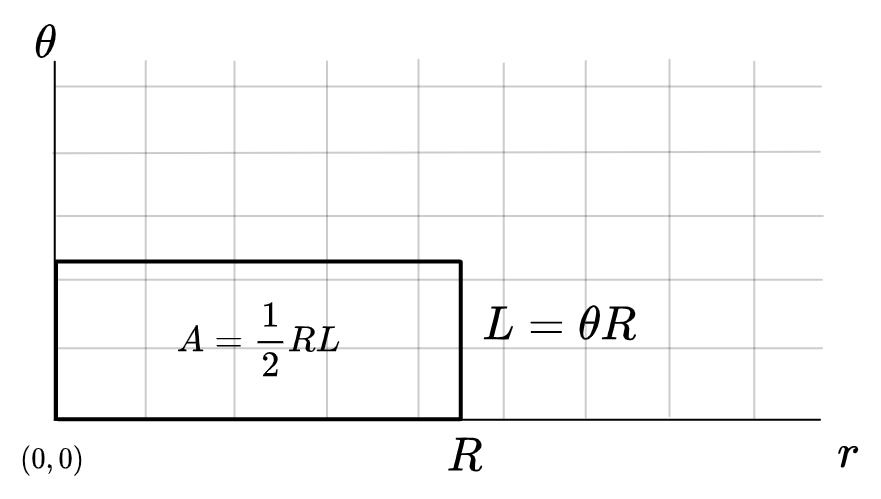

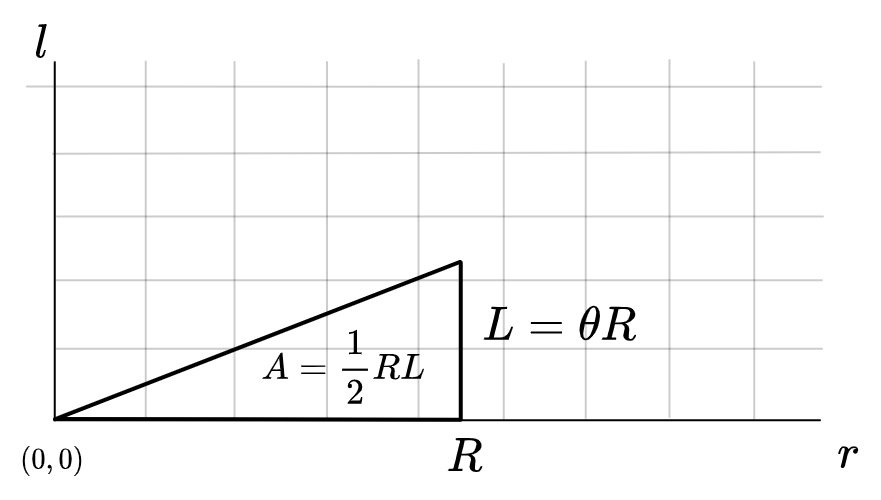

\[\begin{aligned} A &= \frac{\theta}{\bigcirc} (\pi R^2) \\ &= \frac{\theta}{2 \pi } (\pi R^2) \\ &= \frac{1}{2} \theta R^2 \end{aligned}\]A circular arc is a rectangle in polar coordinates:

But in polar coordinates area is not linear: each (infinitesimal) box on the grid has its area weighted linearly by the value of \(r\). The result is that the area is as if it was a true rectilinear box but with half the \(r\) value.

Or we can write this in terms of the length of the arc, \(L = \theta R\):

\[\area = \frac{1}{2} L R\]

Amusingly, this looks like the formula for the area of a triangle with “base” \(L\) and “height” \(R\). This seems a bit weird at first, but there is a way of thinking about it:

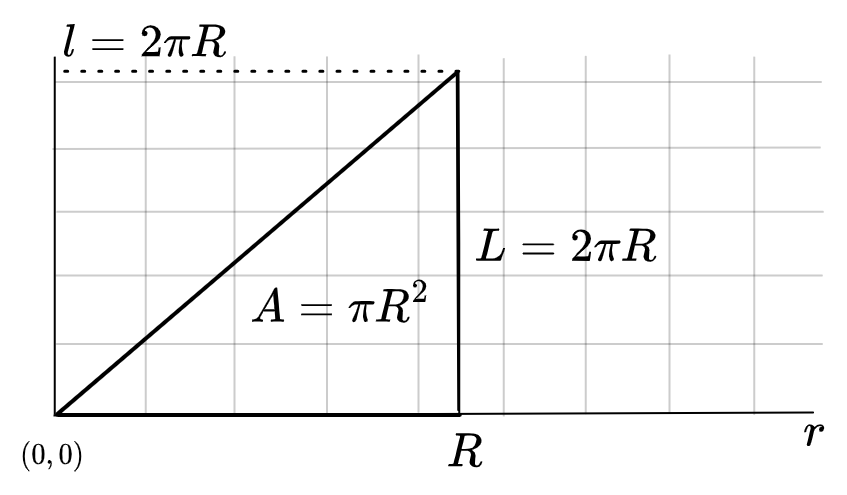

Although polar coordinates do not have boxes of equal area everywhere, it is possible to modify them to another coordinate system which does, in which we use \((r, \ell) = (r, r\theta)\) as the coordinate system. I don’t know of an existing name for this, so maybe we call it “circumference coordinates.” Circumference coordinates multiply the angle value by \(r\) so that, crucially, a box of size \((dr, d\ell) = (dr, r d \theta + \theta d r)\) has area \(1\) everywhere, which means that an arc really is a triangle and can have its area measured with the normal rectilinear area. Which means that when we graph the arc in \((r,\ell)\) coordinates the areas of everything are correct, so it really is a triangle:

And a circle is just a larger triangle:

So it’s suggestive to write the \(\pi R^2\) formula for the area of a circle as

\[\area = \frac{1}{2} CR\]Which just happens to equal \(\frac{1}{2} (2 \pi R) R = \pi R^2\), but kinda gets better at what’s going on.

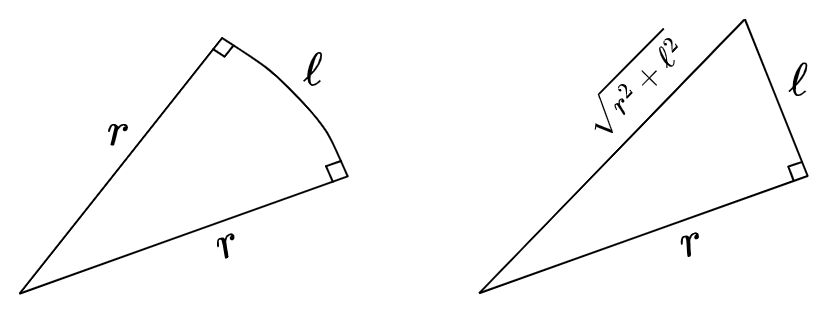

This also means that the triangle area formula also applies to… wavy triangles? (As long as the curved edge is orthogonal to \(\vec{r}\) throughout.)

\(A = \frac{1}{2}r\ell\) either way

I don’t really know what to make of that.

By the way, to compute area as an integral in these coordinates, keep in mind that the \(\ell\) integration bound depends on \(r\), unlike what happens when integrating over \(\theta\):1

\[\int_0^R \int_0^{2 \pi r} d\ell \d r = \int_0^R (2 \pi r) dr = \pi R^2\]What you lose with circumference coordinates is that \(dr\) and \(d\ell = \theta dr + r d \theta\) are no longer orthogonal. These are the directions of constant \(r\) and \(l\); \(d\ell=0\) is close to horizontal away from the origin:

But the area swept out by the two together is still \(1\):

\[dr \^ d\ell = dr \^ d (r \theta) = dr \^ (dr \theta + r d \theta) = dr \^ r d \theta = dx \^ dy\]One reason to keep circumference coordinates in the back of your mind is that any formula that involves \(\theta\) but also involves the length of something essentially has to pair a \(\theta\) with an \(r\) to make it meaningful for measuring length or area. This is for instance why the area element in polar coordinates is given by \(r \d r \d \theta\); it’s really \(dr (r d \theta)\). It’s also you end up with equations like the polar gradient operator,

\[\del f = (\p_r f) \hat{\b{r}} + (\frac{1}{r} \p_\theta f) \hat{\boldsymbol{\theta}}\]This comes from the differential, which has no special factors,

\[df = (\p_r f) dr + (\p_\theta f) d \theta\]But to write it in a basis of unit-length vectors you have to replace \(d \theta\) with \(r \hat{\boldsymbol{\theta}}\), so \(\p_\theta\) becomes \(\p_{\theta}/r\) to compensate. The same thing happens in spherical coordinates with \(r \sin \theta \d \phi\).

3. Atan2

The function \(\theta(x,y)\) gives the polar angle of every point in the \(xy\) plane. It is often used in calculations with the explicit form

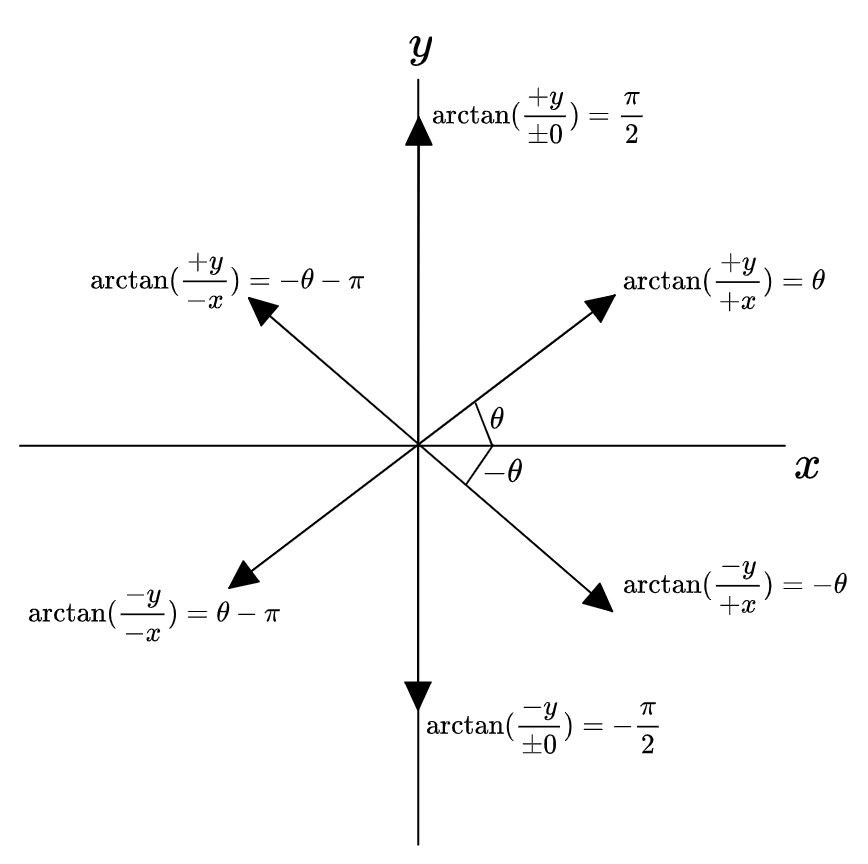

\[\theta(x,y) = \arctan(\frac{y}{x})\]Which gives the correct differential \(d \theta = \frac{x \d y - y \d x}{x^2 + y^2}\). But it is sometimes important to remember that that formula is not correct. In fact \(\arctan\) only gives the angle for half the plane; since both points \((x,y)\) and \((-x, -y)\) give the same ratio \(\frac{y}{x}\), any function of \(y/x\) must make a choice of how to deal with the redundancy. Usually this is by limiting the value to \((-\frac{\pi}{2}, \frac{\pi}{2})\).

Since in practice you often do want the true angle of a point \((x,y)\), programmers have invented atan2 to deal with this redundancy. Unlike \(\arctan\) it is a separate function of each argument, correct to do the right thing:

\[\text{atan2}(x,y) = \{ \theta \; \| \; (x(\theta),y(\theta)) = x,y \}\]Or, more explicitly:

\[\text{atan2}(x,y) = \begin{cases} \arctan(y/x) & x > 0 \\ \arctan(y/x) + \pi & x < 0 \\ \pm \frac{\pi}{2} & x = 0, \; \pm y > 0 \end{cases}\]In picture form:

Of course it is still undefined at the origin, since there is no angle there. The final case unfortunately cannot be covered by defining \(\arctan(\pm \infty) = \pm \frac{\pi}{2}\), because \(y/0\) for \(y>0\) could be either positive or negative infinity in the limit depending on whether \(x \ra 0^{\pm}\). Also, some definitions would add or subtract \(\pi\) as appropriate to keep the values in \([0, 2\pi]\); I’m not too concerned about that because I think of the value as being modulo \(2 \pi\) regardless.

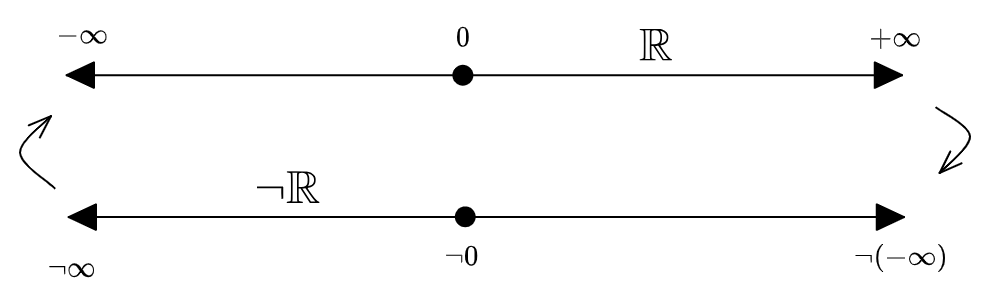

I often find myself wondering about \(\text{atan2}\), because I wonder: is there maybe a way to fix \(\arctan\) so that it takes care of this for us? That is: is there an alternate number system, or a modification of our existing one, such that \(\frac{y}{x} \neq \frac{-y}{-x}\)?

Suppose dividing a negative by a negative is, in some mysterious sense, a different value, which we indicate with \(\neg\), taken to mean \(\neg = \frac{-1}{-1}\). For most purposes \(\neg\) acts like a minus sign, but it has slightly different rules, which we will discuss in a moment. But if we had \(\neg\) available to us then we could define \(\arctan\) just fine: it would be given by

\[\arctan(\neg \frac{y}{x}) = \arctan(\frac{y}{x}) + \pi\]And since \(\frac{+y}{\pm 0} = \neg \frac{-y}{\mp 0}\), this would also work for

\[\arctan(-y/{+0}) = \arctan(y/0) + \pi = 3 \pi/2 \equiv -\pi/2\]By splitting \(\frac{y}{+x}\) and \(\frac{y}{-x}\) into two separate values, we are making the extended real number line \(\overline{\bb{R}}\) into a two-sided line:

Which means that the value \(y/x\) can be used as a coordinate on \(\theta\), and then \(\arctan\) is a \(1{:}1\) change of coordinates between these two.

I have no idea if this number system is well-defined or sensible, or if it’s badly broken somehow. Certainly the regular rules of algebra are all suspect on it. But no one tells you how to define new number systems, unless they’re the typical rings/fields/algebras, and I wouldn’t even know what to look for if I wanted to find a reference on it. But I think about it a lot.

Actually it does exist out there in at least one name: it’s the oriented projective geometry \(\bb{O}^1\) (also written \(\bb{T}^1\) in the literature), which I’ve written a bit about here. In OPG the value of \(y/x\) is also regarded as the tuple \((x,y)\) quotiented by a positive scalar, so \((x,y) \equiv (1, y/x) \equiv (x/y, 1)\) are the same elements; this is evidently equivalent to our construction. (In the more familiar unoriented projective geometry, the equivalence classes are up to a positive or negative scalar, so \((-x, -y) \equiv (x, y)\).) But I don’t know if the OPG model is useful at all either. And the book I read about OPG (by Stolfi) did not talk about doing general algebra with oriented-projective numbers.

Other thoughts:

If \(\arctan(y/x) = \theta\) works everywhere, then the trig functions should do the same the opposite direction: \(\tan \pi/4 = 1\) while \(\tan 5\pi/4 = \neg 1\). I suppose \(\sin\) and \(\cos\) should also, but each would be the ratio of a signed side to the hypotenuse (\(\sin \theta = y/r\), \(\cos \theta = x/r\)), and I can’t see an argument for a hypotenuse to have negative length, hence they are never going to return \(\neg\)‘d values.

I suppose there’s no particular reason to think it’s useful. But it is fun. I’d love to find that there’s some place that this has been investigated, even if it’s just explaining why it doesn’t work.

In the remainder of this article I will write \(\arctan(\frac{y}{x})\) when I mean \(\text{atan2}(y, x)\), cause I’d rather just pretend that it works right.

4. Polar Addition

Here’s something not-very-deep but which I have not really seen written out explicitly before.

A vector in the plane \(\b{x} = (a_x, a_y)\) may be written in polar coordinates as \((r_a, \theta_a)\),2 and, in this basis, you are still allowed to do things like adding vectors together: \((r_a, \theta_a) + (r_b, \theta_b) = (r_a + r_b, \theta_a + \theta_b)\). But you have to be careful about what you mean by this. There is pretty much no relation between \((a_x + b_x, a_y + b_y)\) and \((r_a + r_b, \theta_a + \theta_b)\). If you want their sum as geometric vectors, expressed in polar coordinates, you have to treat them as an \(xy\) vector, via

\[r_a e^{R \theta_a}(\b{x}) = r_a (\cos \theta_a + R \sin \theta_a)(\b{x}) = r_a \cos (\theta_a) \b{x} + r_a \sin (\theta_a) \b{y}\](I am using \(R\) for the rotation operator \(R(\b{x}, \b{y}) = (\b{y}, -\b{x})\). Euler’s formula still holds: \(e^{R \theta} = \cos \theta + R \sin \theta\). Basically \(R\) acts like the \(i\) in complex numbers, but avoids the implications of working in \(\bb{C}\). One could omit the \((\b{x})\) that the whole thing acts on, but I think it’s better to keep it around for aclrity.)

In this form the sum of two vectors just adds them as \(xy\) vectors:

\[\b{a} + \b{b} = [r_a e^{R \theta_a} + r_b e^{R \theta_b}] (\b{x})\]Which, if you like, you can then solve \(r_{a+b}\) and \(\theta_{a+b}\). Or you can compute that from \((a_x + b_x, a_y + b_y)\). They’re given by

\[\b{a} + \b{b} = r_{a+b} e^{R \theta_{a+b}} (\b{x}) = \sqrt{(a_x + b_x)^2 + (a_y + b_y)^2} e^{R \arctan(\frac{a_y + b_y}{a_x + b_x}) }(\b{x})\]Or, in their polar forms, if you really like it messy:

\[\b{a} + \b{b} = \sqrt{r_a^2 + r_b^2 + 2 r_a r_b \cos(\theta_b - \theta_a)} e^{R (\theta_a + \arctan((r_b \sin(\theta_b - \theta_a))/ (r_a + r_b \cos(\theta_b - \theta_a))))} (\b{x})\](If this answer is to be believed; I don’t feel like checking.)

It was not clear to me what’s going on here. Why can you add polar vectors in \(re^{R \theta}\) form and in their \((r, \theta)\) form, and the two mean different things? After some thought I think the explanation goes like this:

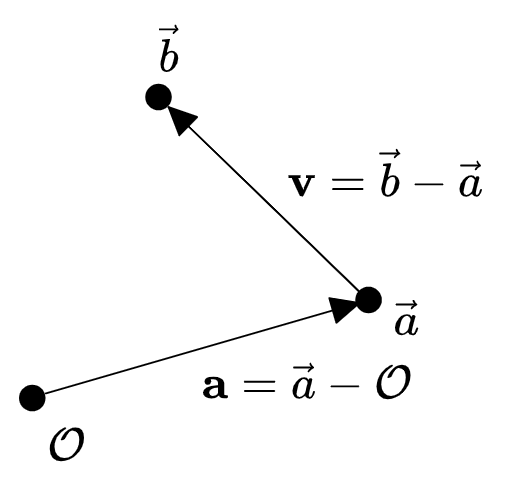

First, we have to distinguish between position vectors and displacement vectors. I will write the two differently: a position will have a vector symbol \(\vec{a}\), while a displacement will be bold \(\b{v}\).

A position vector \(\vec{a}\) measures a displacement relative to a fixed choice of origin \(\mathcal{O}\), but the origin is omitted. You can essentially think of a position vector \(\vec{a}\) as “really” meaning a displacement vector \(\b{a} = \vec{a} - \mathcal{O}\), where the subtraction occurs as abstract points, not in any particular coordinate system, and then the coordinates of the position vector is given by \(\vec{a} = \mathcal{O} + \b{a}\).

A displacement vector, meanwhile, is the difference between the position vectors of two points, where the origins must conveniently cancel:

\[\b{v} \equiv (\vec{b} - \mathcal{O}) - (\vec{a} - \mathcal{O}) = \vec{b} - \vec{a}\]

Subtracting position vectors makes sense because, although each has a hidden factor of \(\mathcal{O}\), the terms cancel. But adding position vectors does not make sense: \(\vec{a} + \vec{b}\) would mean

\[\vec{a} + \vec{b} \? (\mathcal{O} + \b{a}) + (\mathcal{O} + \b{b}) = 2 \mathcal{O} + \b{a} + \b{b}\]Adding two displacements is okay, if their endpoints “chain together”: the endpoint of one term is the starting point of the other.

\[\b{a} + \b{v} = (\vec{a} - \mathcal{O}) + (\vec{b} - \vec{a}) = \vec{b} - \mathcal{O} = \b{b}\]If this condition does not hold, then adding two displacements doesn’t make sense either. For example we could think of two position vectors \(\vec{a}, \vec{b}\) as displacements \(\b{a}\) and \(\b{b}\), but nothing has really changed, so it still shouldn’t work, and it doesn’t:

\[\b{a} + \b{b} \? \vec{a} - \mathcal{O} + \vec{b} - \mathcal{O} \stackrel{??}{=} \vec{a} + \vec{b} - 2 \mathcal{O}\]When I say “does not make sense”, I don’t mean the sense that you will hear from mathematicians sometimes, that an operation such as division by zero or taking a certain limit doesn’t make sense because a definition hasn’t been provided for it. Instead it is more like a failure of units matching up, comparable to adding kilograms to meters, or like a program in a programming language failing to typecheck. You can certainly define a mathematical setting in which two values of diferent units are addable if you want, but it won’t have any physical meaning. Similarly, although vectors’ components can be added as numbers, there is no physical meaning unless one vector ends where the other one starts.

In Euclidean coordinates, every vector (displacement and position) looks like every other vector, and the unit vector directions are the same at every point in space, so we tend to allow ourselves to add any two vectors together: \(\b{a} + \b{b} = (a_x + b_x, a_y + b_y)\), no problem. But if this operation is to survive generalization, it is important that we think of it in a coordinate-invariant way. What we’re actually doing is saying: there is a coordinate system \((x,y)\) which produces a vector field \((\hat{\b{x}}, \hat{\b{y}})\), and our vectors represent translations proportional to those vectors; adding our vectors without any fanfare encodes the claims that (a) any two points in the space can be canonical identified, so that displacements which start at different points having meaning, and (b) any two translations in these coordinates commute and can therefore be added as scalars: \((a_x, a_y) + (b_x, b_y) = (a_x + b_x, a_y + b_y)\). Essentially we think of a vector \(\b{a}\) in Euclidean coordinates as an operator: increase \(x\) by \(a_x\) and \(y\) by \(a_y\). When we do this we (implicitly) claim that the \((x,y)\) coordinate system is meaningful everywhere: increasing \(x\) at one point means the same thing as increasing it everywhere else. That is, we have moved to a quotient space: we are treating every tangent plane as identical. This only works if they, well, actually are.3

The same property does not hold in curved coordinates. Translating by \((r, \theta)\) means something different depending where you are in space; the unit displacements change as you move around. Treating a polar vector \((r_a, \theta_a)\) as a translation really means something like more: apply two operators, one which increases the radius by \(r_a\) and the other which increases the angle by \(\theta_a\). These operations are also composable, of course. But the key point is that the two representations give different operators: the addition of \(\b{a}\) in Euclidean coordinates is not at all the same operation as the addition of \(\b{a}\) when written in polar coordinates. In \((x,y)\) coordinates \(\vec{a}\) and \(\b{a}\) mean the same thing; in \((r, \theta)\) they do not.

Nevertheless there are times when you do want to add polar coordinates to each other. For instance the differential of a function in \((r, \theta)\) coordinates uses it:

\[\begin{aligned} d f &= f_r \d r + f_{\theta} \d \theta \\ &= [\lim_{\Delta r \ra 0} \frac{f(r + \Delta r, \theta) - f(r, \theta)}{\Delta r}] \d r + [\lim_{\Delta \theta \ra 0} \frac{f(r, \theta + \Delta \theta) - f(r, \theta)}{\Delta \theta}] d \theta \end{aligned}\]But this works because all of the addition happens locally, in the tangent plane, which looks flat: \(\p_r\) and \(\p_\theta\) refer to constant directions if you zoom enough.

In my opinion although we generally write vectors out in a coordinate system like \(\b{a} = a_x \b{x} + a_y \b{y}\), it is best, if you are trying to solve some puzzle about their interpretation, to think of them as being explicitly identified with translation operators in that coordinate system, like

\[\b{a} = a_x T_{x} + a_y T_{y}\]When you go to change coordinate systems, the coordinates change, but so do the operators. In polar coordinates \(\b{a}\) becomes

\[\begin{aligned} \b{a} &= r_a e^{R \theta_a} (T_x) \\ &= r_a (\cos (\theta_a) T_x + R \sin (\theta_a)) T_y \\ &= r_a \cos( \theta_a )T_x + r_a \sin (\theta_a) T_y \end{aligned}\]Which is the same object, and not at all the same object as \(r_a T_{r} + \theta_a T_{\theta}\).

(In differential geometry this is all done by using partial derivatives themselves as the basis for vectors, like \(\b{a} = a_x \p_x + a_y \p_y\). It’s the same idea, but I think it’s not necessary to make sense of what’s going on. Also, since everything happens in the tangent plane, you can e.g. compute the length of the vector with \(\| \b{a} \| = \sqrt{r_a^2 + r^2 \theta_a^2}\) without worrying about non-linearity. For finite displacements it is much weirder: the length depends on where the displacement starts and finishes in a very non-linear way.)

A related weirdness happens if you try to do regular linear algebra with vectors written in different coordinate systems. For instance we know that the rotation operator is given in \((xy)\) coordinates as

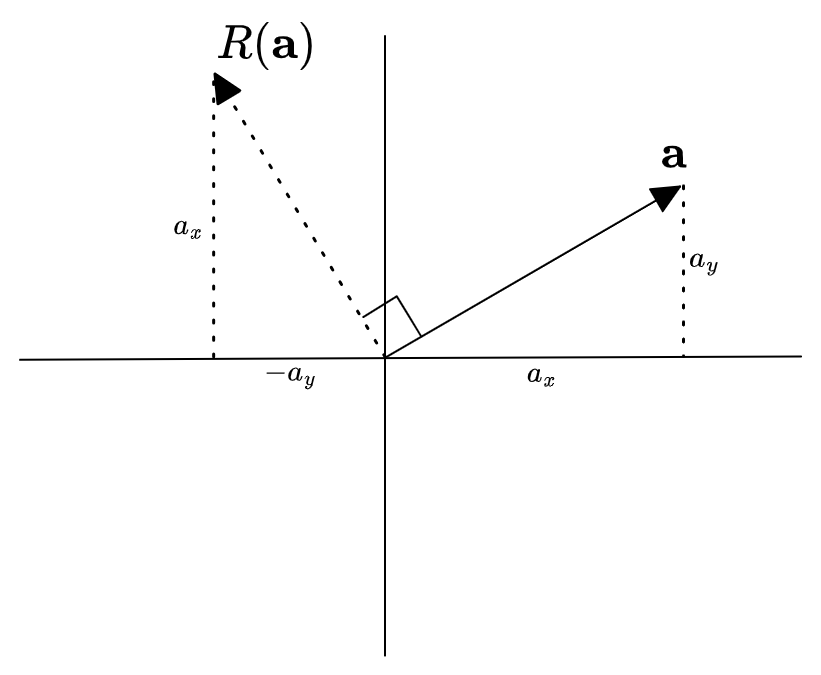

\[R = \begin{pmatrix} 0 & -1 \\ 1 & 0 \end{pmatrix}\]Which gives

\[R (\b{a}) = \begin{pmatrix} 0 & -1 \\ 1 & 0 \end{pmatrix} \begin{pmatrix} a_x \\ a_y \end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} -a_y, a_x \end{pmatrix}\]

When writing \(\b{a}\) in polar coordinates as \(\b{a} = (r_a, \theta_a)\), you may try to translate \(R\) into the same coordinates. We know the right answer:

\[R(r_a, \theta_a) = (r_a, \theta_a + \pi/2)\]But you can’t… really…. write it as a matrix?

\[R \b{a} = \begin{pmatrix} 1 & 0 \\ 0 & \text{???} \end{pmatrix} \begin{pmatrix} r_a \\ \theta_a \end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} r_a \\ \theta_a + \pi/2 \end{pmatrix}\]Because the \(\theta\) coordinate is additive instead of multiplicative.

I know of a few solutions:

- Write \(\theta_a\) as \(e^{R \theta_a}\), so that multiplying by by \(e^{R \pi/2}\) gives \(e^{R(\theta_a + \pi/2)}\)

- Use a homogenous representation, in which \(\b{a} = (r_a, \theta_a, 1)\) and then the rotation operator can “dip into” the \(1\) to implement translations.

- This is how vector translations are often represented in computer graphics: by adding a dimension to a vector space you can represent affine transformations (linear transformations plus translations) using \(4 \times 4\) vectors and matrices, which turns out to be very handy.

- Declare that in polar coordinates, angular coordinates add instead of multiply, so \((0, \pi/2) \times (r_a, \theta_a) = (r_a, \theta_a + \pi/2)\).

- Another way of thinking of this is by saying: it just happens that in linear algebra we use “multiplicative” coordinates, but we can always create take the logarithm of some of our coordinates and use that instead, in which case they’re going to have to add instead of multiplying.

- Incidentally there is a thing called log-polar coordinates in which you take the log of both polar coordinates.

It seems to me that (3) is the general and appropriate solution, while (1) and (2) are hacks to work around being afraid of it. This is contrary to how most fields actually do things, though.

Anyway, I’m sure this is studied to death somewhere out there, but it’s the sort of thing that might not occur to you going through the standard math curriculum. And I guess I would prefer that linear algebra was taught in such a way that this would not be a surprise: even the definitions of multiplication and linearity are, in a way, coordinate-dependent.

5. Angles as Vectors

In the previous section I was using \(R\) to represent the rotation operator, and sticking it in exponentials, etc, in much the way that \(i\) is used in \(\bb{C}\):

\[e^{R \theta} \b{x} = (\cos \theta + R \sin \theta) \b{x} = \b{x} \cos \theta + \b{y} \sin \theta\]I prefer this because \(i\) is irksome in many ways. The interesting thing about \(\bb{C}\) is how it algebraically completes \(\bb{R}\) by adding an additional dimension, and then functions in terms of \(z \in \bb{C}\) are extremely well-behaved (the best example being that a “radius of convergence” in \(\bb{C}\) is actually a radius of something! And also that most of 1d calculus continues to work on analytic functions of \(z\), mostly-unchanged). In my mind \(\bb{C}\) is primarily interesting because of how it interacts with analysis: holomorphic functions, poles, series and convergence, etc. But if you’re just trying to talk about plane geometry, you really don’t need any of that, and you really just want to be using \(\bb{R}^2\) with a rotation operator.

In particular \(\bb{C}\) conflates two different objects in \(\bb{R}^2\): it identifies vectors \(a \b{x} + b \b{y}\) with operators on vectors \(a I + b R\). This is fine, I guess, but it is helpful to keep them distinct if you want everything to be sensible. It also helps you be aware of what’s going to generalize to higher dimensions naturally versus requiring repairs.

When you replace \(i\) with \(R\), the trigonometric functions get new definitions:

\[\begin{aligned} \cos (\theta) &= \frac{e^{R \theta} + e^{-R \theta}}{2} \\ \sin (\theta) &= \frac{e^{R \theta} - e^{-R \theta}}{2 R} \\ \tan (\theta) &= \frac{1}{R} \frac{e^{R \theta} - e^{-R \theta}}{e^{R \theta} + e^{-R \theta}} \\ \end{aligned}\]Which to me are (a) fun and (b) suggestive of some interesting underlying structure.

For one thing, if you were in \(\bb{R}^3\), there is a basis of three rotation operators \(\vec{R} = (R_{yz}, R_{zx}, R_{xy})\). So maybe there would be multiple sines and cosines in terms of any of them, which would have some algebraic relationships to each other. I don’t know if this is a thing out in the literature, but anyway it’s fun so let’s see what it does. Well, it’s related to the usual quaternion representation of rotations… but I like the idea of redefining sine/cosine/etc, and I don’t know of that being a thing. But I imagine it works like this:

An angle \(\theta\) is replaced with an angle times a rotation operator \(R\) which refers to the axis of rotation: \(\vec{\theta} = \theta R\). I’m not sure this is quite the right way to represent it, but clearly an angle ought to incorporate its direction somehow, so we’ll just say it comes along as a factor. This is the equivalent of writing a vector \((a_x, a_y)\) with its basis included, as \(a_x \b{x} + a_y \b{y}\), creating a coordinate-invariant object. (Note that if you rescale \(R\) you have to change units on \(\vec{\theta}\); \(R\) evidently encodes the choice of “radians” as the unit.)

To implement Euler’s Formula, we use the hyperbolic sine and cosine instead, since the \(R\) is inside the argument still:

\[\begin{aligned} e^{\vec{\theta}} &= \cosh \vec{\theta} + \sinh \vec{\theta} \\ &= \cosh R \theta + \sinh R \theta \\ \end{aligned}\]Although it is not the case that this equals \(\cos \theta + R \sin \theta\). Consider a rotation generator in \(\bb{R}^3\) like \(R_{xy} = \big(\begin{smallmatrix} 0 & -1 & 0 \\ 1 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 \end{smallmatrix}\big)\). Its square is not the negative identity, but a projection onto \(xy\): \(R_{xy}^2 = \big(\begin{smallmatrix} -1 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & -1 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 \end{smallmatrix}\big) = -I_{xy}^2\). This is the case for any rotation operator \(R\): its powers will project onto the plane it rotates in. So we can write \(R^2 = -I_R\) and \(R^4 = I_R\). The Taylor series \(e^{\vec{\theta}} = e^{R \theta}\) shows us that the equivalent of Euler’s formula is

\[\begin{aligned} e^{\vec{\theta}} &= 1 + (R \theta) + (R \theta)^2/2! + (R \theta)^3/3! + (R\theta)^4/4! + \ldots \ldots \\ &= \cosh R \theta + \sinh R \theta \\ &= I_{\perp R} + I_{R} \cos \theta + R \sin \theta \\ \end{aligned}\]where \(I_{\perp R}\) is the identity on vectors not in the plane of \(R\). This is essentially the content of the Rodrigues formula for rotations. Doing things this way, with a generator that squares to a projection, avoids the weird stuff that happens with quaternions that necessitates using a half-angle formula \(\b{v} \mapsto e^{q\theta/2} \b{v} e^{-q\theta/2}\) for rotations.4

We can still define the sine function for a rotation the same way:

\[\begin{aligned} R \sin \theta &= (e^{R \theta} + e^{-R \theta})/2 \\ \sin_R \theta &= (e^{R \theta} - e^{-R \theta})/(2R) \\ \end{aligned}\]But the cosine is weirder. We’d have to use one of these:

\[\begin{aligned} \cosh R \theta &= (e^{R \theta} + e^{-R \theta})/2 \\ I_{\perp R} + I_R \cos_R \theta &= (e^{R \theta} + e^{-R \theta})/2 \\ \cos_R \theta &= I_R (e^{R \theta} + e^{-R \theta})/2 \end{aligned}\]It’s semi-common to write 3d rotations around an arbitrary axis as a vector in a basis of rotation generators, so the exponent looks like either \(\vec{\theta} \cdot \vec{R}\) or \(\theta \b{n} \cdot \vec{R}\), with \(\b{n}\) as the unit normal for the rotation. (Not to be confused with the quaternion/geometric algebra/Pauli matrix approach, where the exponent is an element of a Cliffor algebra.) They all express the same idea. In our notation it would look like

\[\begin{aligned} e^{\vec{\theta}} &= e^{\theta_{xy} R_{xy} + \theta_{yz} R_{yz} + \theta_{zx} R_{zx}} \\ &= \cosh \vec{\theta} + \sinh \vec{\theta} \\ &= \cos \theta + \frac{\vec{\theta}}{\| \theta \|} \cdot \vec{R} \sin \| \vec{\theta} \| \\ &= \cos \theta + (\b{n} \cdot \vec{R}) \sin \theta \end{aligned}\]with \(\theta = \| \theta \|\) as the angle itself and \(\vec{R} = (R_{yz}, R_{zx}, R_{xy})\) as the vector of generators.

I think these oriented angles and the formulas that arise from them clarify things. It makes the algebra more honest about what it’s doing. But I’m still confused about the difference between doing it this way and with the seemingly-more-complicated Clifford Algebra approach. Although, speaking of…

6. Trig Functions as Tensor Operators

Here’s a somewhat weirder idea that goes further in the same direction.

There are several ways of “dividing vectors” out there, which I’ve written about a bit before. I haven’t figured out how to sort them all out exactly, but in this section we’re going to use the Clifford/geometric product on only vectors, which has a fairly simple and agreeable exposition.

Consider how we could assign meaning to the operator \(\b{b}/\b{a}\), which ought to have \((\b{b}/\b{a})\b{a} = \b{b}\) for some sense of multiplication. If the numerator is allowed to distribute, we can factor

\[\b{b} = \b{b}_a + \b{b}_{\perp a} = (b \cos \theta) \hat{\b{a}} + (b \sin \theta) R \hat{\b{a}}\]Where \(\theta\) is the angle between \(\b{a}\) and \(\b{b}\) and \(R\) is the rotation operator in the plane spanned by the two. Then division might look like this:

\[\begin{aligned} \frac{\b{b}}{\b{a}} &= \frac{\b{b}_a}{\b{a}} + \frac{\b{b}_{\perp a}}{\b{a}} \\ &= \frac{b \cos \theta}{a} \frac{I \hat{\b{a}}}{\hat{\b{a}}} + \frac{b \sin \theta}{a} \frac{R \hat{\b{a}}}{\hat{\b{a}}} \\ &\? \frac{b}{a} I \cos \theta + \frac{b}{a} R \sin \theta \\ &= \frac{b}{a} e^{R \theta} \end{aligned}\]Which has

\[\frac{\b{b}}{\b{a}} \b{a} = \frac{b}{a} e^{R \theta} \b{a} = b e^{R \theta} \hat{\b{a}} = \b{b}\]Here the sense of division we’ve used is to extract operators in the expressions \(\hat{\b{a}}/\hat{\b{a}} = I\) and \(R \hat{\b{a}}/\hat{\b{a}} = R\). As far as I can tell, this is the basic operation that is implemented by the Clifford product. But I suspect that this is not he only way to do it. One could also imagine a division operation that has \(\hat{\b{a}}/\hat{\b{a}} = I_a\), the projection onto the subspace of \(a\), and \(R \hat{\b{a}}/\hat{\b{a}}\) as an operator which takes \(\hat{\b{a}} \ra R \hat{\b{a}}\) but \(R \hat{\b{a}} \ra 0\). I’m not sure yet how to organize this all so that it makes sense, but anyway, when you allow the division to take the form of full-rank linear operators, you get \(I\) and \(R\), and the resulting division operation looks like the Clifford product \(\b{b} \frac{1}{\b{a}} = \b{b} \cdot \frac{1}{\b{a}} + \b{b} \^ \frac{1}{\b{a}}\).

Another way of thinking about this is that we’re computing the ratio of the vectors in their polar representations, but be careful, the sense of subtraction here is not the usual vector one.5

\[\begin{aligned} \frac{\b{b}}{\b{a}} &= \frac{b e^{\vec{\theta}_b} (\b{x})}{a e^{\vec{\theta}_a} (\b{x})} = \frac{b}{a} e^{\vec{\theta}_b - \vec{\theta}_a} = \frac{b}{a} e^{R \theta} \end{aligned}\]We could also imagine factoring the denominator. It should give the same thing, which we accomplish by multiplying through by \(e^{R\theta}/e^{R \theta}\).

\[\begin{aligned} \frac{\b{b}}{\b{a}} &= \frac{\b{b}}{(a \cos \theta) \hat{\b{b}} - (a \sin \theta) R \hat{\b{b}}} \\ &= \frac{\b{b}}{a e^{-R \theta} \hat{\b{b}}}\\ &= \frac{b}{a} \frac{e^{R \theta} \hat{\b{b}}}{\hat{\b{b}}} \\ &= \frac{b}{a} e^{R \theta} \end{aligned}\]I have no idea about the exact rules of calculus when it’s done this way (I’ve diverged from the GA presentation somewhat)… but there’s clearly something to it.

An interesting correlary of this is that, just like \(e^{R \theta}\) is an operator that takes \(\hat{\b{a}}\) to \(\hat{\b{b}}\), the trigonometric functions themselves seem to be interpretable operators which operator on the projections. Suppose we’re talking about the \(xy\) plane, then

\[\begin{aligned} \b{a} \cosh \vec{\theta} &= \b{a} \frac{a_x \b{x}}{\b{a}} = a_x \b{x} = (a \cos \theta) \b{x} \\ \b{a} \sinh \vec{\theta} &= \b{a} \frac{a_y \b{y}}{\b{a}} = a_y \b{y} = (a \sin \theta) R \b{x} \\ (a_x \b{x}) \tan \vec{\theta} &= (a_x \b{x}) \frac{a_y \b{y}}{a_x \b{x}} = a_y \b{y} = (a_x \tan \theta) \b{y} \\ \end{aligned}\]Which are clearly the “geometrized” versions of the trig relations of cosine=adjacent/hypotenuse, sine=opposite/hypotenuse, etc. So the “geometrized” trig functions \(\cosh \vec{\theta} = I_{z} + I_{xy} \cos \theta\) and \(\sinh \vec{\theta} = R_{xy} \sin \theta\) are themselves tensor operators and elements of the Clifford Algebra.

I like this. It often seems like everything we do with elementary algebra is just a projection out of a tensor-algebra-like thing which has many of the same rules, but which is much more consistently type-safe: \(\cos \theta\) takes a hypotenuse in that plane to its projection in that plane; to use it anywhere else requires, essentially, parallel-transporting it there, which could in some curved setting change its value, the same way lengths are not directly comparable in differential geometry. And the algebraic identities end up also being geometric identities: not only are they true facts, but they are constructive procedures for producing one side from the other, when the types and vectors are restored everywhere. Something like that? I dunno. Just a feeling. But it’s all too cute to not be a good idea somehow.

-

Aside, you can also replace \(d \ell\) with its average value in the \(r\) integral, which is \(d \ell/2 = ds\). This leads to the semiperimeter area formula \(A = \int r \d s = rs\) for polygons, where \(r\) is the radius of the inscribed circle/length of the apothem. ↩

-

I think it’s vaguely more aesthetic to use \((r_a, \theta_a)\) instead of \((a_r, a_\theta)\) when working in polar coordinates. ↩

-

What’s going on “under the hood” is that position vectors represent points on a (Lie Group) manifold, while displacement vectors represent straight lines between points (or non-straight lines, since you can pick a coordinate system in which any particular line is straight anyway). The two have the same data in \(\bb{R}^n\), but that is essentially a fluke: it so happens that in flat spaces with trivial topology we can represent a point as a displacement from a fixed origin, so their data is the same. But in general there is no direct quantitative relationship between them at all. ↩

-

Quaternion rotation vectors (and geometric algebra) have \(q^2 = -1\), which is the negative identity on the whole space, rather than a projection, and the half-angle formula keeps things working on the part of \(\b{v}\) that’s not in the plane of rotation. I have so far failed to understand why this works for the cases where it does; the behavior of quaternion/geometric algebra multiplication is much stranger than that of the simple linear operators I’m using here. So I find these easier to understand, at least for this case. ↩

-

The sense of “subtraction” on \(\vec{\theta}_b - \vec{\theta}_a\) is related to the stuff in section (4). Since we are taking the difference of rotation operators, we want to produce a rotation-displacement that takes \(\vec{\theta}_a\) to \(\vec{\theta}_b\), which ought to be \(R \theta\), the rotation that we’ve specified to take \(\b{a}\) to \(\b{b}\) on the \(R\) plane. But this does not mean subtracting componentwise in the \((\theta_{yz}, \theta_{zx}, \theta_{xy}) \cdot (R_{yz}, R_{zx}, R_{xy})\) representations, unless the two rotations happen to commute. Normally this is expressed by not allowing them to be combined in the exponent at all, like \(e^{\vec{\theta}_b} e^{-\vec{\theta}_a}\), but IMO the real problem is just with the notion of “subtraction” on the components of a vector. Anyway, to get the precise value you can write both rotations out their sines and cosines and then multiply them out, quaternion-syle. Or use the BCH formula. (edit: this is kinda wrong but it’s going to take me a while to fix. TLDR for \(e^{\vec{\theta}_a} e^{-\vec{\theta}_b} = e^{R \theta}\) to work, we need each rotation to fix the rotation of the whole frame in a consistent way, not only the \(\b{x}\) vector.) ↩